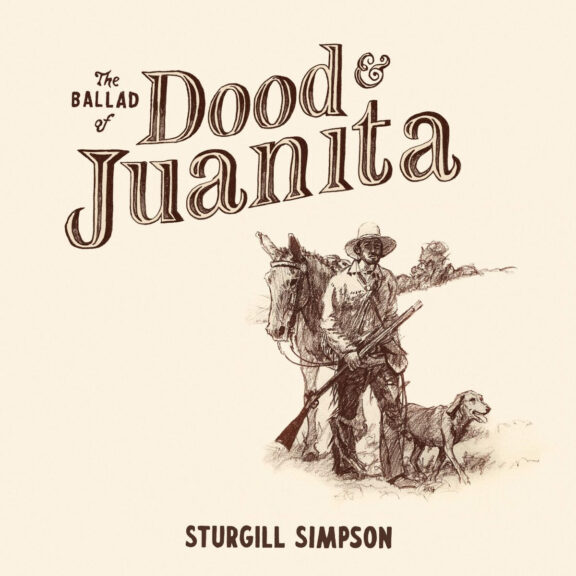

Whether you attribute it to Mark Twain or regard it as an Irish aphorism, there’s something to be said for the idea of not letting truth get in the way of a good story. Based on his real-life grandparents and falling somewhere between “Pancho and Lefty,” the Coen Brothers’ Ballad of Buster Scruggs, and the forgotten crevices of Appalachia, Sturgill Simpson’s fifth (and final) solo album The Ballad of Dood and Juanita takes that concept and runs.

It’s a short and distinctive project, wrapping up at just under half an hour for ten tracks that tell a start-to-finish story about love and revenge in the 1860s (Simpson’s grandparents, after whom the album is named, didn’t actually live the fictional tale). Sonically speaking, the album should placate fans who prefer High Top Mountain over Sound and Fury. It’s a healthy exchange between bluegrass and old-timey country, dancing with both but never running too far in one direction.

Simpson and his team of “Hillbilly Avengers,” the musicians he paired up with for his Cuttin’ Grass volumes, bring Dood, Juanita, Shamrock, and Sam to life in cinematic detail. Dood is a larger-than-life, sharpshooting son of a miner father and Shawnee mother; dramatic fiddle and banjo become his backdrop, emulating the flicker of the campfire around which you can imagine this story being told.

Springy, fast-paced instrumentation sets the scene for Shamrock, an enormous mule that “didn’t need no kick to go,” and accentuates his role in Dood and Juanita’s mini-drama. For Sam, Dood’s dog, his turn in the spotlight comes in the form of a solemn, almost a-capella homage. “Sam” is perhaps the most marked departure, but over the course of the album the changes in tone between each track create the feeling that listeners are watching acts of a play. The curtain drops during the pause between each song, only to be rolled back up on an entirely new, yet still connected, vignette.

Simpson told Rolling Stone that he originally thought of writing the story as a Western, but opted to create something more tailored to his own roots: an “Eastern.” Nonetheless, the instrumentation in “Juanita” toes that line. The track’s languid strings, a guitar solo from Willie Nelson, and ocean-themed lyrics are more evocative of a Mexican beach than an Appalachian mountain. Standing as a testament to Simpson’s creativity, this contrast highlights the incongruity that Juanita herself presents: “Juanita, where’d your momma get that name/there’s no señoritas from the mountains where you came.” The track also features the album’s standout vocal performance, as Simpson’s voice soars at some points to match Dood’s longing, and fades into the distance at others, emphasizing that Juanita is still out there somewhere waiting to be found.

While the detailed songwriting gives the identity of each character an importance equal to that of the story itself, the plot-oriented songs tie everything together. Simpson’s voice softens slightly for “One in the Saddle, One on the Ground” as he recounts the events that set everything in motion. Through the ups and downs in songs like “Played Out” and “Go In Peace,” the album captivates with rich, mood-setting arrangements.

Co-produced by Simpson and David Ferguson, the traditional-leaning concept album lives in territory where Simpson has previously thrived – both structurally and sonically. Just as the story of Dood and Juanita comes full circle, so does the odyssey that began in 2013 with High Top Mountain. While some listeners may have expected something bigger for Simpson’s final solo album, The Ballad of Dood and Juanita is a fitting choice for the final bookend in the five-album series. It illustrates the only two consistencies of Sturgill Simpson: one, that he’s never going to do what you expect from him, and two, whatever he does is top quality. As a creative force to be reckoned with, there’s no doubt that Simpson is going to continue to build on the indelible mark he’s already left on several different genres with the collaborative projects he takes on in the future.